History Repeats l Zika Is a Reminder Of Why We Immunize.

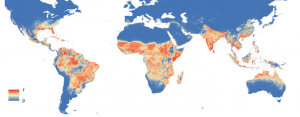

Global distribution of the mosquito Aedes aegypti. (Image: Wikipedia Commons.)

History Repeats

In 1941, an Australian ophthalmologist by the name of Norman Gregg noted a mini-epidemic of a rare eye disorder (“congenital cataract”) in newborn infants referred to him for treatment. Intrigued, he went looking for a cause. What he discovered astonished him – and the rest of the medical profession. It turned out that most of the mothers of these unfortunate infants had contracted Rubella (“German Measles”) during their first trimester of pregnancy. Rubella infection in adults is generally no big deal; symptoms are “flu-like,” and self-limited in duration. Gregg’s observations led to the realization that rubella – a mild disorder for the pregnant mother – could be devastating to her fetus. Other infectious agents capable of causing severe fetal damage were soon added to the list. (In Med School I was taught the acronym “TORCH” – standing for Toxoplasmosis, Rubella, Cytomegalovirus, and Herpes – as a way of remembering these agents.)

By its nature, rubella strikes in waves, spreading rapidly among susceptible children, and striking adults who had not been infected as children themselves. In 1962, the last epidemic year for rubella, approximately 20,000 infants were born in the United States with Congenital Rubella Syndrome (CRS): microcephaly, generalized growth failure in the womb, congenital heart disease, congenital cataracts, and intellectual disability. Rubella vaccine was introduced in 1969. Mass immunization of susceptible children terminated epidemic rubella in the US, and all but eliminated the risk of rubella exposure among pregnant women. Essentially no new cases of CRS are occurring within the US at this time. (Occasional cases are still reported among American women who were exposed to rubella overseas, where the disease is still rampant.) Elimination of CRS is thus an American medical success story.

Now, along comes Zika virus. Zika virus was discovered in equatorial Africa (Uganda, Nigeria, Central African Republic, etc.), first in rhesus monkeys (1947), and subsequently in humans (1968). Soon thereafter Zika virus was also noted in tropical countries in the Far East (India, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam). In the wild, both humans and non-human primates (e.g. the rhesus monkey) form the reservoir for Zika virus, and the virus is spread via the bite of several species of mosquito. (Human-to-human spread via sexual intercourse has been documented in one case; how much of a risk this poses remains to be seen.) Zika infection was a sporadic issue until 2007, when the rate of new human cases suddenly spiked (possibly due to a mutation within the viral genome, conferring greater infectivity). Not only did the rate of occurrence of new cases shoot up (the definition of an epidemic), the geographical distribution of Zika also expanded, to include the Caribbean and Central and South America – all zones hospitable to the mosquito vectors of the disease (Figure). Most recently, we are discovering that Zika, like Rubella, can be devastating to the fetus, resulting in severe impairment of brain growth (“microcephaly”). The precise developmental consequences of intrauterine Zika infection remain to be determined, but if our experience with TORCH agents is any guide, these infants face an increased risk of cerebral palsy, intellectual disability, seizures, hearing impairment, and other neurodevelopmental issues.

What is to be done?

Curtailing mosquito activity is one standard public health measure against all mosquito-transmitted diseases (e.g. malaria, yellow fever, West Nile virus, etc.). Unfortunately, climate change (“global warming”) works in the mosquitos’ favor, steadily enlarging their habitable range. International travel and commerce also provide channels for exportation of mosquito-borne illness to previously uninfected areas. Immunization against the virus itself is not currently available. As long as Zika was regarded as a nuisance illness of poor countries, the prospect of immunization was dim. Now that we see the ramifications in terms of fetal morbidity, and now that Zika is on America’s doorstep, that situation may change. But development of immunizations takes time, and some viruses are capable of mutating quickly (influenza, HIV, e.g.), making it difficult or impossible to stay ahead of them with immunizations. For now, a woman’s safest course is to avoid travel to areas known to be endemic with Zika if she is pregnant or considering becoming pregnant. Long-range fetal risk (i.e. if a woman is bitten months or years before becoming pregnant), and risk via sexual transmission or other forms of human-to-human contact remain to be worked out. (Complete CDC guidelines).

Zika is a reminder of why we immunize, and a jolting return to the scary days of the 50s and 60s, when devastating epidemic disease (polio, rubella) held sway. It is also a demonstration of (viral) evolution and global warming in action. (For a prescient, and terrifying, overview of how we have gotten to where we are today in the public health area, read The Coming Plague and Betrayal of Trust, both written by Laurie Garret.) Our elected leaders owe us science-based intervention rather than science denial, in response to this pressing public health menace.

James Coplan, MD is an Internationally recognized clinician, author, and public speaker in the fields of early child development, early language development and autistic spectrum disorders. Join Dr. Coplan on Facebook and Twitter. Have a question for Dr. Coplan? Ask the doctor.

Leave a Reply