ASD and Crime: More on risk factors

Picking up where we left off last time:

ASD and Crime: Risk Factors

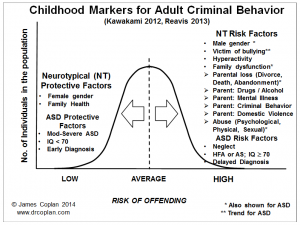

Higher functioning ASD, Asperger Syndrome, and IQ in the normal range carried a greater risk than classical autism and IQ below 70. Is one “increased” or is the other “decreased”? Hard to say. It’s possible that the individuals with HFA / AS are more prone to criminal behavior for some reason. Conversely, individuals with classical autism and/or intellectual disability have limited unsupervised access to the community, and therefore little opportunity to commit crime. Both factors may be relevant. This leads back to my point a few posts ago about why we shouldn’t fixate on some “average” risk, since this “average” may be composed of very different subgroups. (Anything published before 1994 is based on the DSM-III-R definitions of autism and PDD-NOS, which are skewed towards lower-functioning kids. The “explosion” in diagnosed cases of ASD, and the increasing proportion of kids with high functioning ASD and/or Asperger Syndrome came after the publication of DSM-IV [1994], and the implementation of IDEA [1990]. Thus, the older literature appeared to lend some support to the claim that persons with autism don’t commit violent crime, or do so at a lower rate than the general population. Now that the reported prevalence of ASD exceeds 1%, and the composition of the ASD population has shifted so that the majority of persons on the spectrum have mild atypicality and IQs in the normal range, all bets are off in terms of the older literature. Go back to my previous post and read what Mouridsen and Woodbury-Smith have to say about the complete absence of meaningful epidemiologic data: https://www.drcoplan.com/elliot-rodger-what-we-know-and-what-we-dont )

Delayed diagnosis was also a risk factor. Did lack of services during the early school years set some kids on a downward path? Perhaps they were subjected to disciplinary reprimands rather than autistic support services? Or could delayed diagnosis be a marker for some wider problem, such as family dysfunction? We just don’t know.

Parental loss and physical abuse were risk factors in both atypical and neurotypical subjects. Neglect, on the other hand, carried no apparent risk for neurotypical subjects, but was the single biggest risk factor for children on the spectrum: Children in the “Criminal” group were 15 times more likely to report that they had been neglected than non-criminal controls.

(Does this mean that if you have gone through a divorce, or if your child’s ASD was not diagnosed until age 10, that he or she is doomed to a life of crime? Of course not. These are associations, not absolutes. And the more we know, the better we will be able to mitigate risk.)

Writing about the impact childhood adverse events in neurotypical children, Reavis had this to say:

What about these early events is so damaging? … It is our belief that mediating variables between the adverse event and the criminal outcome are neurobiologic dysregulation and attachment pathology… Accumulating adverse experiences in one’s childhood decreases an individual’s subsequent ability to form secure attachments to others…In some boys, the intensely negative feelings stimulated by poor treatment from their attachment figures are associated with either an avoidance of intimacy, or a “bleeding out” of the feelings into their intimate relationships [as adults], in the form of violence.

What about the child on the autism spectrum, who starts out with neurobiologic dysregulation and impaired attachment? Could this be why “Neglect” spiked out so dramatically in the ASD subjects, while it didn’t even register a blip with the NT subjects? Or, perhaps there was no actual neglect, but the subjects who went on to criminal behavior felt that they were being neglected. (The questionnaire, after all, was based on self-report.) Perhaps the perception of neglect is tied to the degree of social impairment: difficulty perceiving parental attention may be on the flip side of the coin from difficulty relating to people. We just don’t know. How many of us have ever asked a child on the spectrum: “Do you feel neglected?” Maybe we should start!

This brings us to the subject of the core features of ASD, and how they may be interacting with environmental variables.

More next time.

References

1. Reavis, J.A., et al., Adverse childhood experiences and adult criminality: how long must we live before we possess our own lives? The Permanente journal, 2013. 17(2): p. 44-8.

2. Kawakami, C., et al., The risk factors for criminal behaviour in high-functioning autism spectrum disorders (HFASDs): A comparison of childhood adversities between individuals with HFASDs who exhibit criminal behaviour and those with HFASD and no criminal histories. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 2012. 6(2): p. 949-957.

James Coplan, MD is an Internationally recognized clinician, author, and public speaker in the fields of early child development, early language development and autistic spectrum disorders.

Leave a Reply