Beyond Kanner and Asperger – part 1

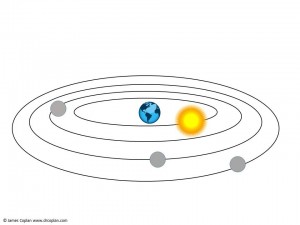

Figure 1. Until the Middle Ages, most people believed that the earth was at the center of the universe (the geocentric model).

Dr. Coplan proposes a paradigm shift in the way we frame our thinking about ASD.

For the past several posts (beginning here), we have been reviewing Steve Silberman’s book, NeuroTribes. As Silberman points out, persons with High Functioning Autism and Asperger Syndrome are far more common than heretofore recognized. Furthermore, there is no “bright line” dividing “atypical” from “Neurotypical” (NT). Rather, “mild atypicality” shades over, imperceptibly, into “normal.”

Silberman highlights the differences between Kanner’s formulation of ASD (rare and severe) with current thinking (diverse and common). What’s missing, however, is an over-arching frame of reference, within which we can think comprehensively about all different forms of expression of atypicality – not only persons with AS, but persons with old-fashioned “Kanner-type” autism. “If you’ve met one person with autism, you’ve met one person with autism.” True enough, but there are some underlying features in common, and it is helpful to be able to think about both similarities and differences among people with all degrees of ASD, at all ages. To do this will require a change in our overall way of looking at the situation – a “paradigm shift.” Paradigm shifts have happened before. Perhaps the best example comes from astronomy.

From the days of the ancient Greeks until the Middle Ages, most people believed that the earth was stationary, and all other celestial bodies revolved around it. This way of framing the situation seemed intuitively obvious: the sun and moon certainly appear to “rise” and “set” each day; conversely, the earth does not fling us off into space, as we might expect if it were travelling at thousands of miles per hour through the heavens. But as the ability to make astronomical observations improved, it became evident that the sun, moon, and stars did not behave exactly as would be predicted with the geocentric model. To account for these discrepancies, astronomers proposed something called epicycles. (To get an idea of an epicycle, imagine that the Meter Maid has marked one of your tires with chalk. Remove the tire from your car, and roll it around the outside of a gigantic barrel. As you roll the tire around the barrel, the chalk mark travels in a big circle around the barrel, but at the same time it also travels in its own little circle around the axis of the tire. Go here for an animation; scroll down and press the “Play” arrow). Eventually, however, this way of describing the movements of celestial bodies became too cumbersome, as astronomers kept adding epicycles on top of epicycles in a never-ending effort to reconcile their observations with the assumption that the earth was at the center of things.

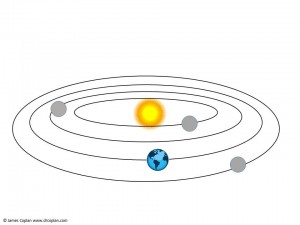

Then along came Copernicus, who in the early 1500s proposed the model of the solar system that we know today, with the sun at the center (“heliocentric”). The heliocentric model didn’t alter the way the individual celestial bodies were described: The sun still had a corona, the moon still had craters, Mars was still the Red Planet, and so on. Rather, what changed was the relationship between the various bodies. This shift in frame of reference revolutionized astronomy. Lots of things “fell into place” that had been difficult to explain under the old, geocentric model. (Eventually, Keppler showed that planetary orbits were elliptical, rather than circular, but this was still infinitely simpler than epicycles, which were relegated to the dustbin of history.) New ideas often meet with resistance. It took over 200 years before science and the Church could be convinced to abandon the earth-centric model, during which time Copernicus and his followers paid a heavy price. Some were ridiculed. Some were burned at the stake for the crime of heresy. Galileo was forced to recant his belief in the heliocentric model or face excommunication (although reputedly declaring under his breath “And yet it moves” – referring to the earth).

Figure 2. The heliocentric model of the solar system as proposed by Copernicus.

Like the shift from the geocentric to heliocentric model of the solar system, I propose a paradigm shift in the way we “frame” ASD. The description of ASD itself does not change: echolalia is still echolalia; stereotypies are still stereotypies, and so on. Rather, what changes is the relationship between ASD and a couple of other key variables. I do not expect to be burned at the stake, and I don’t have to worry about being excommunicated. Nonetheless, there is something called the NIH (“Not Invented Here”) Syndrome. So I am prepared for the fact that it may take a while for my frame of reference to be adopted by the Powers that Be. Hopefully just not 200 years.

More next time.

(Continue to part two.)

James Coplan, MD is an Internationally recognized clinician, author, and public speakerin the fields of early child development, early language development and autistic spectrum disorders. Join Dr. Coplan on Facebook and Twitter. Have a question for Dr. Coplan? Ask the doctor.

Leave a Reply