Beyond the DSM: Seeing ASD in 3D, Part II

A lot has happened since I posted Part I of this thread. I grieve for all of the families in Newtown who lost loved ones. I will have more to say about those events shortly, but in order for my comments to make sense, we need to finish laying the groundwork.

In Part I of this thread, I described the X axis of a graph, on which I displayed the symptoms in the four areas impacted by ASD: Social, Language, Repetitive Behavior, and Sensorimotor. The child’s development in these four areas is off the track (“atypical”). Notice that there’s nothing on the X axis about IQ. That’s because atypicality is separate from IQ. Because IQ is independent of atypicality, we put IQ on its own axis:

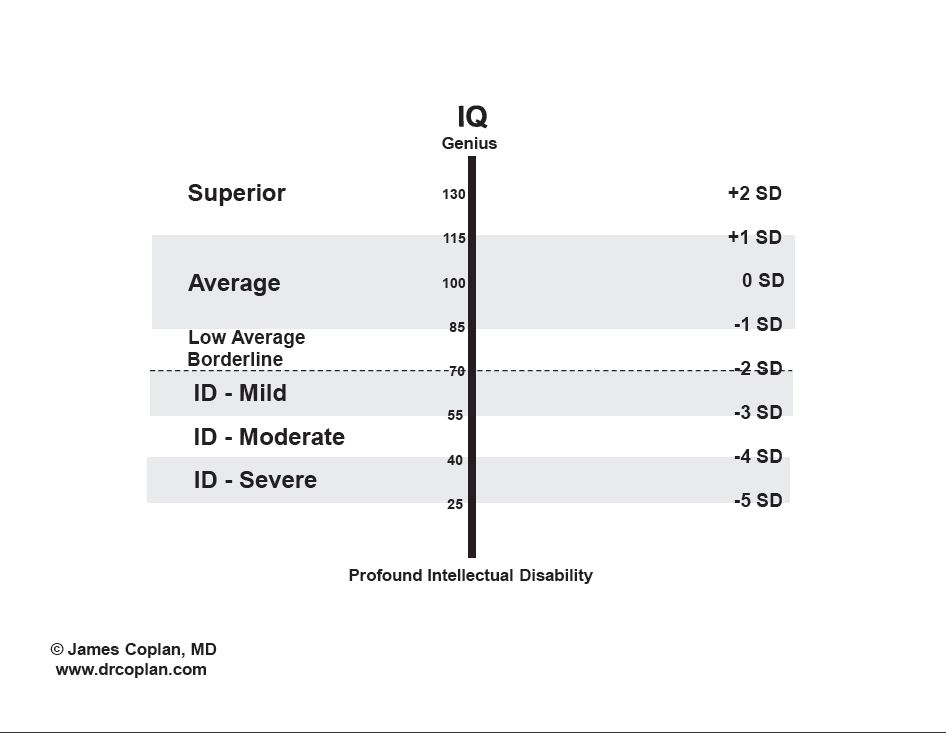

Figure. IQ scale.

IQ tests are designed so that the average (“mean”) score = 100. The “spread” in scores above or below the mean is described in “standard deviations” (SD). On most IQ tests, 1 SD = 15 points. Intellectual Disability is defined in part by having an IQ score that is 2 or more SD below the mean (i.e., less than 70). This is roughly the same as the 2nd to 3rd percentile. At the other end of the scale, persons with IQ’s of 130 or higher are performing at or above 97th to 98th percentile, relative to the population as a whole. (Based on “Making Sense of Autistic Spectrum Disorders,” figure 5.2)

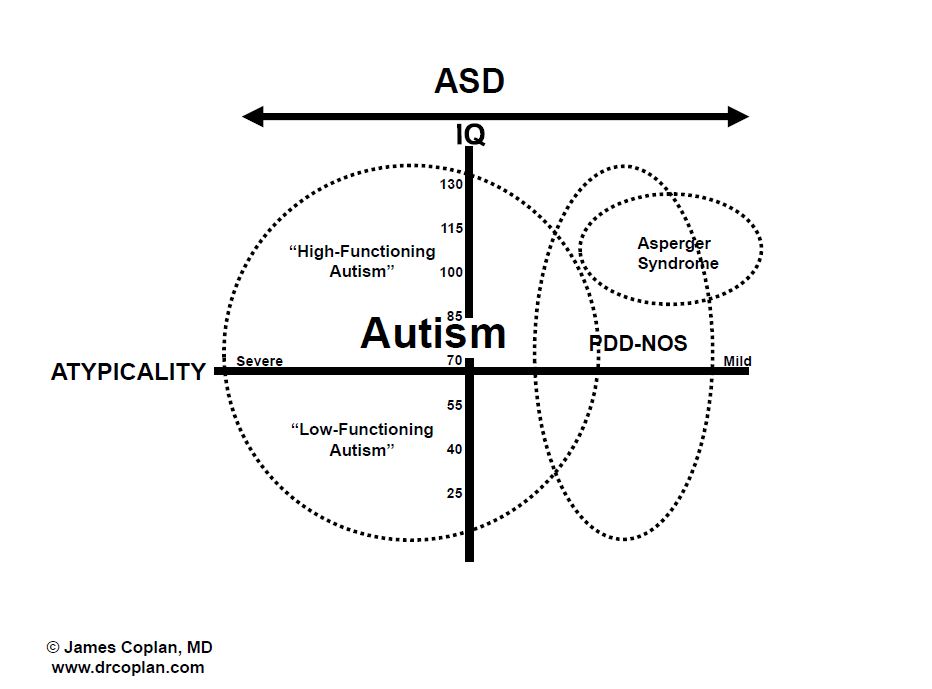

An individual can have any combination of intelligence and atypicality, just as someone can have any combination of height and weight. Another way to think about the relationship between IQ and atypicality is to imagine that you are waiting for a train: The train may be late, on time, or ahead of schedule; this corresponds to the overall rate of intellectual development (IQ). Additionally, the train may have one or more wheels off the track; this corresponds to atypicality. Each is important, but they are separate issues. In order to depict this relationship visually, we combine the X axis (atypicality) and the Y axis (IQ). Now we have an XY graph, on which we can map each child’s unique combination of atypicality and IQ.

Figure. XY graph, depicting the relationship between degree of atypicality on the X axis, and level of intelligence on the Y axis.

We have also displayed the regions that roughly correspond to the terms autism, PDD-NOS, and Asperger Syndrome. Persons with severe-moderate atypicality combined with an IQ of 70 or greater have what’s known colloquially as “high functioning” autism, while those with severe-moderate atypicality combined with IQ below 70 are said to have “low-functioning” autism. Persons with Asperger Syndrome are hyperverbal, while persons with autism and PDD-NOS are hypoverbal. The DSM-V will be eliminating all of these individual terms, making it all the more important to describe IQ as well as atypicality when characterizing an individual’s development.(Based on “Making Sense of Autistic Spectrum Disorders,” figure 5.4).

Long-term outcome is driven by the combined effect of degree of atypicality and IQ. In some cases, the person’s atypical features will fade to the point where he or she no longer meets criteria for a diagnosis of ASD. However, this does not mean that such individuals are “cured.”

More on these topics next time. If you want to “read ahead,” view this clip:

The entire webinar, “Autism Spectrum Disorder across the lifespan,” can be viewed here or on my home page.

Leave a Reply