Bright’s Disease, ASD, and the Dustbin of History

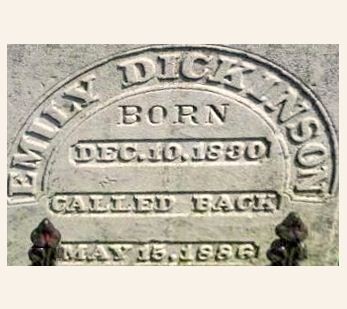

In 1886 the beloved American poet Emily Dickenson died of “Bright’s Disease”- the popular term in those days for kidney failure. No one dies of Bright’s Disease these days – Not because kidney failure has been eradicated, but because it has been broken down into dozens of specific disorders, each with its own cause and form of treatment, thereby relegating “Bright’s Disease” to the ranks of discarded medical diagnoses, along with ptomaine poisoning , consumption, and falling sickness. Each of these obsolete diagnoses referred to a specific symptom or set of symptoms (edema, in the case of Bright’s Disease) that was considered the hallmark of the disorder. In each case, however, medical science eventually produced a deeper understanding of the problem: Often, it turned out that a specific biological factor could give rise to many different symptom patterns (or, no symptoms at all, in some individuals). Conversely, sometimes different biological factors produced identical symptoms. Therefore, even though two patients might have identical symptoms their treatments might vary, because of this difference in underlying cause (we don’t give antibiotics to treat viral pneumonia, for example). Eventually, the original, symptom-based diagnoses were discarded, in favor diagnostic formulations based not just on symptoms, but on mechanisms of biological causation.

We are at the same point today, trying to diagnose ASD on the basis of atypical behavior, as physicians were 150 years ago, trying to diagnose pneumonia by the smell and color of the patient’s sputum. And, like Bright’s Disease, “Autism” and “ASD” are nothing more than catchall terms that lump dozens of disparate disorders under one label based upon similarity of symptoms, without regard to the underlying biology. Even if we were to achieve a consensus on the essential symptoms necessary to diagnose or rule out ASD, our logic would be circular, and circular logic proves nothing. Let me give you an example of what I’m talking about: Most of the birds that congregate at the birdfeeder outside my window are brown. Adult male cardinals stand out from all the other birds, because of their bright red plumage. What if I were to define “cardinals” based on the color pattern of adult males? I could create a terrific diagnostic test based on that definition, that accurately detected 100% of adult male cardinals, with no false positives and no false negatives, but I would still miss half of all adult cardinals, and 100% of the chicks (since red plumage is not present in adult females, or chicks of either gender). This is the curse of a behavioral definition for ASD, rather than a definition rooted in biology. We focus on the most obvious symptoms (the “red plumage” of ASD, if you will), but with no regard for the deeper connections between apparently disparate disorders: Why do some children with ASD manifest intense sniffing behavior? Why are some children hyperverbal, while the majority are hypoverbal? Why do some persons with ASD have co-existing Intellectual Disability, Anxiety Disorder, or Tics, and others not? And the over-arching question: Is the male to female ratio of ASD really 3 to 1? Or do females with the same underlying biology just look different from males, and therefore, like brown cardinals, get labeled something else? And if so, is that a good thing or a bad thing? And what does all this say about treatment?

Granted, we need to start somewhere. We cannot – as Humpty Dumpty once claimed – let words mean whatever we choose to let them mean. On the other hand, we need to guard against becoming too invested in this year’s behavioral definition of ASD – or next year’s (although funding for services usually hinges on “getting the diagnosis,” so behavioral criteria can have practical consequences). Rather, our goal should be to get at the underlying biology – at which point “autism” and “ASD” can join Bright’s Disease in the dustbin of medical history.

Leave a Reply