What ever happened to “People First”?

So far, most of the criticism of DSM5 has focused on specific changes in the definition of ASD: Collapsing Language and Social impairment into a single category, elimination of Asperger Syndrome, etc. In an Orwellian fashion, even though the term “Autism Spectrum Disorder” suggests a bigger, more inclusive tent, in reality the net effect of these changes will be to shrink the number of persons who qualify for services. However, rather than focusing on these issues (as egregious as they are), we have a couple of larger concerns, which thus far seem to have escaped notice, or public discussion:

First (and as a physician myself I cringe to say this), is the American Psychiatric Association’s “deficit model” of ASD: ASD is a strictly a disorder, not a way of being. Unless you are significantly impaired, you can’t have ASD. In every other branch of medicine, we have persons with “asymptomatic” stages of disease: The person whose nasopharynx is colonized with strep bacteria, but who is not ill, for example. Not so with DSM5, where symptoms are not just one aspect of a condition. Rather, symptoms are the condition.

Second, as the inevitable consequence of this “pathology first” (as opposed to “People First”) model, DSM5 comes off as deeply muddled on the subject of the natural history of ASD – i.e., the predictable improvement in persons with ASD over time. On one hand, DSM5 correctly notes that although symptoms of ASD are typically present from the earliest stages of child development, they “may not become fully manifest until social demands exceed limited capacities” — for example, the preschool child who seems fine at home but does not join his or her peers at Circle Time, or the 3rd grader who begins to flounder as reading comprehension requires not just rote learning but the ability to make inferences from the text. Likewise, when it come to making a diagnosis of ASD in an older child or adult, DSM5 acknowledges that “symptoms change with development,” and stresses the importance of searching the early developmental history for evidence of repetitive behavior that may no longer be present. On the other hand (if DSM5 is to be believed), neither time nor therapies make a difference. Rather, symptoms in adults are “suppressed,” or “masked” by “learned strategies.” Did it ever occur to the authors that some symptoms really go away? Or that adults with ASD may have learned to “adapt to” rather than “mask” their neurobiology? And perhaps even thrive?

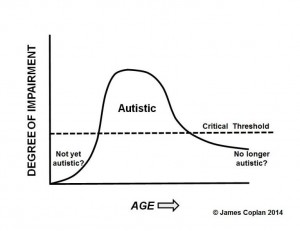

Here is DSM5’s view of the universe (the picture is mine; it does not appear in DSM5): On the horizontal axis we have age. On the vertical axis we have “Degree of Impairment.” I have indicated a “critical threshold” with a dashed line. Unless an individual’s atypicality crosses that threshold, he or she cannot have ASD (per the DSM).

(Click on graph to see Full Screen)

On the left are young children who have not yet “grown into” a diagnosis of ASD. I see this in the office all the time: The 2 year old with speech delay and the “flavor” of atypicality, who does not meet criteria for ASD. Over the next several years, the gap between the child and his peers widens. Eventually, a spectrum diagnosis becomes inescapable. On the right side of the figure are adolescents and adults who have shed their stereotypies, echolalia and sensory issues. Some of them are employed, and married. Some of them are the parents of my pediatric patients! What do we call the youngsters on the left, and the adults on the right? If DSM5 is to be taken literally, there are three classes of individuals: “Not yet ASD,” “ASD,” and “No longer ASD.” Even an adult who used to have prominent repetitive behaviors when younger would not qualify for a current diagnosis of ASD, unless that adult is currently “significantly impaired.” This view of the world jars my sensibilities. Call me an old codger, but I think we should bring back “Autism, residual state” (present in DSM-III, and removed in DSM-III-R), to encompass the individuals on the right. More on that another day.

1. Mazefsky, C.A., et al., Brief Report: Comparability of DSM-IV and DSM-5 ASD Research Samples. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 2013. 43(5): p. 1236-1242.

2. Kulage, K.M., A.M. Smaldone, and E.G. Cohn, How Will DSM-5 Affect Autism Diagnosis? A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-analysis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 2014.

3. Volkmar, F.R. and B. Reichow, Autism in DSM-5: progress and challenges. Molecular Autism, 2013. 4(1): p. 13.

James Coplan, MD is an Internationally recognized clinician, author, and public speaker in the fields of early child development, early language development and autistic spectrum disorders. Join Dr. Coplan on Facebook and Twitter.

Leave a Reply