Internalizing

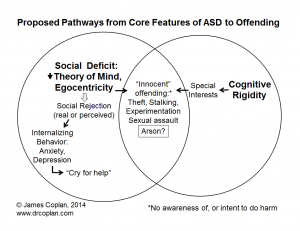

Click on figure to view full size.

Dr. Coplan maps the connections between social rejection, internalizing behavior, and suicide risk in persons with autism spectrum disorder. Internalizing behavior usually does not trigger criminal offending, but it can be the prequel to violent externalizing behavior.

The British psychiatrist Lorna Wing passed away last month, after a long career dedicated to bettering the lives of persons with ASD, including her own daughter. It was Lorna Wing who in 1981 coined the term “Asperger Syndrome.” This blog post is dedicated to her memory and legacy.

Here is the list of factors Dr. Wing enumerated as contributors to crime committed by persons on the spectrum (I have re-ordered the items):

1. Assumption that the person’s own needs supersede all other considerations

2. Lack of awareness of wrongdoing

3. Intellectual interest (what Asperger himself called “Autistic acts of malice”)

4. Pursuit of “special” interests (objects, people)

5. Vulnerability

6. Cry for help

7. Hostility towards family

8. Hyperarousal

9. Revenge

In our last post on the subject of ASD and crime, I introduced the term “innocent offending” to describe criminal behavior stemming from the combination of obsessive interests and lack of social awareness (Items 1-4 in Wing’s list). Here, I’ve added another pathway to the diagram, this time leading from social rejection to internalizing behavior.

Click on figure to view full size.

“Internalizing behavior” is all the emotional stuff we hold inside. Anxiety and depression are the prime examples of internalizing behavior. Individuals with ASD have a biologically built-in vulnerability to depression, even under the best of circumstances. On top of that, most individuals with ASD face social rejection at some point in their lives. (Note the qualifier “or perceived” in the diagram. In Kawakami’s study, the perception of neglect was 15 times higher among youth with ASD plus crime compared to youth with ASD who had not committed crime. Whether they were actually neglected remains to be determined. However, the depression and bitterness that ensue are real, even though the original perception may have been distorted.)

Anxiety and depression can be immobilizing. Alternatively, a person with depression may become so distraught that they start engaging in agitated, disruptive, or self-destructive behavior as a “cry for help” (items 5 and 6 in Wing’s list). Risk-taking, cutting, attempts at self-medication via legal or street drugs, and suicide gestures or attempts are all examples of “cries for help.”

The top 3 causes of death in adolescents and young adults with neurotypical development are accidents, homicide, and suicide (and many “accidents” are probably covert suicide). Depression is common in ASD, yet we know almost nothing about suicide risk in youth with ASD. A recent study in Lancet conducted among adults with newly diagnosed Asperger Syndrome found that 66% had entertained thoughts of suicide, and 35% had made plans on how kill themselves, or carried out a suicidal attempt, at some point in their lives. These data are not drawn from a randomly selected subset of persons with AS, so they may not apply to all persons with AS or high-functioning autism, but they are deeply concerning.

Internalizing behavior does not typically lead to crime. Unfortunately, internalizing behavior is often ignored – until it erupts into externalizing behavior. More on that next time.

1. Wing, L., Asperger’s syndrome: Management requires diagnosis. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry, 1997. 8(2): p. 253-257.

2. Kawakami, C., et al., The risk factors for criminal behaviour in high-functioning autism spectrum disorders (HFASDs): A comparison of childhood adversities between individuals with HFASDs who exhibit criminal behaviour and those with HFASD and no criminal histories. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 2012. 6(2): p. 949-957.

3. Cassidy, S., et al., Suicidal ideation and suicide plans or attempts in adults with Asperger’s syndrome attending a specialist diagnostic clinic: a clinical cohort study. The Lancet Psychiatry, 2014.

James Coplan, MD is an Internationally recognized clinician, author, and public speaker in the fields of early child development, early language development and autistic spectrum disorders.

Leave a Reply