Special Children, Part 2

Dr. Coplan explains the concept of “special children,” and why having a “special child” makes it more difficult for parents to adapt to the presence of disability.

Be sure to read Special Children, Part 1 first.

Imagine a wagon train heading west. In order to reach California, the wagon master needs to find a pass over the mountains – the lowest possible route, to minimize the climb and avoid hazards such as blizzards, avalanches, etc. In a similar fashion, families need to find a pass over the mountain range of adapting to the birth of a new baby – whether disabled or not. Especially if it’s their firstborn child, old patterns of behavior (such as sleeping through the night!) go out the window, and new ones emerge, as the adults shift from being a couple, to being parents. The emotional landscape also changes, as new relationships are formed and old ones are reconfigured. Dad may feel a bit left out at out at first, as mom is focused on the new arrival. If it’s the second child, then child #1 may feel some jealousy as well (When our second child was a few months old, our firstborn accused my wife of being “a bad mother” for bringing home a new baby!). The first few months can be pretty hectic. However, if all is well the family eventually settles into a new and satisfying emotional rhythm.

But what if all is not well? Now the parents have two tasks: grieving the loss of the anticipated perfect baby, while adapting to the baby they have, who presents unforeseen challenges, and whose future is under a cloud. No two families are exactly alike, but there are recognizable stages in this process (This sequence was initially described by Elisabeth Kubler-Ross within the context of fatal illness, rather than the birth of a child with disability. One key difference is that fatal illness has an endpoint, while rearing a child with special needs does not.): Immediately after the shock of recognition of a problem, parents may enter a period of denial (A brief period of denial is normal, and gives the body time to gather strength for what is to come), quickly followed by anger (“Why my child?”), guilt (“What did I do wrong?”) or blame (“It’s got to be somebody’s fault”). Soon, however, these feelings are overshadowed (although not entirely replaced) by a need to engage in positive action. Parents may remain chronically stressed by the demands and worries associated with rearing a child whose needs are greater than average, and may continue to experience continual or intermittent bouts of sadness (“Chronic Sorrow”). But in one fashion or another, their lives go on, with at least with some semblance of normality.

Some parents, however, never make it through the adaptation process. Like those unfortunate pioneers who perished along the trail west, they remain mired in perpetual grief, guilt, anger, blame, magical thinking, or, in extreme cases, denial.

Why do some parents get stuck? Typically, there is something about the situation that increases the difficulty of the adaptation process. It may be something specific to the parent (pre-existing parental depression, for example), or, it may have more to do with the circumstances surrounding the child. These are the kids I refer to as special children.

Below, I’ve listed some of these factors. This list is not exhaustive, nor is it absolute: Think of the psychological challenge of adaptation (the emotional “mountain pass,” if you will) as a big “U.” The bottom of the “U” is the lowest route to the other side. It’s still a challenge, but the bottom of the “U” offers the best shot to get across. The further away from that mid-point a family lies, the harder the climb, and the greater the risk of getting stuck.

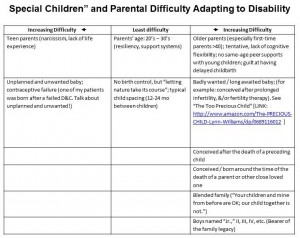

“Special Children” and Parental Difficulty Adapting to Disability

(Click to enlarge!)

Families that have not adapted successfully behave in characteristic ways, depending on where in the process (shock, denial, anger, guilt, blame) they have become stuck: The parent on an endless quest for “the right diagnosis” (or a cure), the angry parent, for whom no caregiver is good enough, the over-dedicated parent who lives entirely for the sake of their child (“selflessness” is often a way of counteracting guilt or anger), and the workaholic parent, who wards off despair by immersing themselves in their day job, are common manifestations of unsuccessful adaptation.

At the start of my career, I used to feel frustration, anger, or dread when “stuck” families came my way: “Why don’t they understand? Why don’t they listen to me?” Now I approach the situation like a detective: “What’s the missing piece of the story that accounts for why this family is stuck?” The parents’ behavior may be self-defeating or destructive, and on the surface may seem illogical. But Mother Nature does not spend energy for no reason. Dig deep enough, and there’s an explanation. And within the context of that explanation, the parents’ behavior makes perfect sense. Sometimes I can figure it out, and help the family get un-stuck. Sometimes, even though I see the problem, the family is so entrenched in its way of doing things that I am unable to make a difference. But that’s the subject of another blog.

Until then.

James Coplan, MD is an Internationally recognized clinician, author, and public speaker in the fields of early child development, early language development and autistic spectrum disorders. Stay connected, join Dr. Coplan on Facebook and Twitter.

How do parents get un-stuck from “selfless” step of the process. The fear of Autism and the unknown for a child who one day looks almost NT, and one day has “atypical” time…is over whelming. The mild borderline child is very preplexing…feeding the denial and then the imminent ASD confirmation. Life became a string of what ifs…and we can’t get out of it. How does a “healthy” ASD parent look and feel…when their kid is “different”?